Neil Yeargin, President, ITT Interconnect Solutions

The spark came to James Cannon when he was sixteen years old.

It was 1906, and Cannon, a high school dropout from Utah, decided to move to California and try his hand at electricity. He took an electricity course in Monterey, and, before he knew it, was hooked. He was an instant talent.

Soon, Cannon became assistant to the engineer at the Del Monte Hotel power plant and made sure the lights never went out during heavy rain (the main line ran through the dirt and under a bridge from the power plant to the hotel). He went on to work for an electrical supply house, where he would become manager at the age of 18.

After he landed a job at a large electrical contractor working as a designer of specialties, he realized he could do more than the average electrical engineer, and set out to make specialty electrical parts on his own.

One hundred years ago, Cannon sparked a life changing idea – to become an entrepreneur.

In 1915, he started the Cannon Electric Development Company in a small backroom space in Los Angeles and unknowingly embarked on a path that would make him one of the greatest innovators of the last century. There, in that space, Cannon spent many late nights sleeping on his desk because – so lost in thought or engrossed in work – he missed the last streetcar home.

Cannon’s early inventions ranged from an electric toaster (The Hot-’N Hot), to the first telegraphic fire system for the city of Los Angeles.

When the wartime economy nearly bankrupted him, he didn’t close up shop. After borrowing $100 from a friend to finance a location change, he moved his company headquarters to an even more humble location – a 15-by-16 foot backyard shed he converted into an electrical workshop. To friends and family, he jokingly called the cold and dark space “the morgue.”

His belief in his business was driven by an insatiable desire to invent. He had an innovative mind and sophisticated understanding of all things electrical that was far ahead of his time. His slogan on his calling cards was “Do It Electrically!”

Cannon’s most memorable spark came in 1923, when he invented the M plug. Now backed by five other investors and working from a two-story plant, he engineered a four-pole plug that revolutionized the electronics industry. It featured a “floating contact” that made it possible for microphones that house it to be kicked or moved around, without creating any noise in the recordings.

Indeed, the floating contact may be the greatest contribution to the connector industry. The invention turned the “Cannon plug” into a generic name still used today, and laid the groundwork for a series of previously unimaginable innovations across almost every industry.

Lights, Camera, Sound!

The M Series connector was originally designed to be a quick method to ground the electrical motor on portable meat grinders, but it was Hollywood that really made the plug a star. Movie studios had begun using the connectors to allow their new electrical cameras to move around freely while continuing to shoot without disrupting the image. The M connectors were used for electrical circuits including synchronous camera motors, microphone circuits and camera blimps.

Then, in the mid-1920s, as moviemakers began experimenting with sound pictures, they employed smaller versions of the M Series in sound equipment. As the M series evolved, its smaller versions were incorporated into sound equipment, helping make possible the first “talkie” movie, The Jazz Singer, in 1927. The movie, starring Al Jolson, heralded the decline of the silent film era.

The marriage of speed, reliability and ingenuity at Cannon paid off when an engineer from Fox Studios stopped in to ask if Cannon could make two different microphone plugs in a hurry. The incumbent supplier, Western Electric, was promising a six-week turnaround. James Cannon countered with an offer: “I’ll have them in two weeks. They’ll be a little different and a lot better.”

True enough, the resulting F Series connector met the needs for Fox Studios – the new design, which incorporated the floating contact, allowed sound engineers to avoid variations in contact resistance when the fittings were moved during recording. All the movie studios – and radio stations – ended up using the Cannon F plugs, and even Western Electric became a huge customer.

The F audio connectors were soon followed by P Series connectors, developed for Paramount Studios. This series represented a trend toward smaller and more compact connectors and a huge step forward in design. The P connector incorporated many construction features still in use today: die-cast shells, molded pin inserts and latch-locking devices. The P-Connector was also Cannon’s first patent.

Soon, Cannon was supplying audio and video connectors to all emerging forms of entertainment – the K connector made possible the first TV camera of the 1940s and the LKT connector was used on the first color TV equipment in the 1950s.

At one point during the 1940s, it was estimated that every American was using a Cannon connector at least five times a day – to watch television and movies, listen to the radio, to fly or to fight for their country.

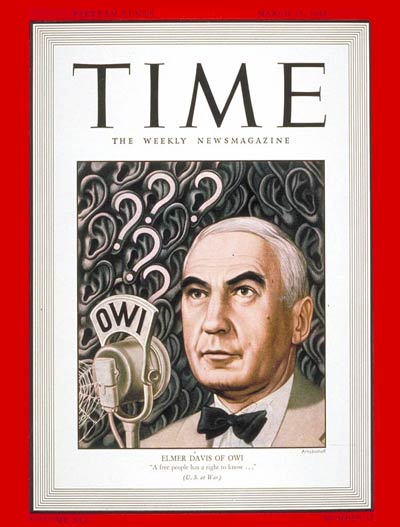

The Cannon connector not only made history during this time, it was immortalized on the cover of Time Magazine – On March 15, 1943, the cover of Time had an illustration showing Elmer Davis, Director of the United States’ Office of War Information, speaking into a microphone (with a Cannon XL connector) to symbolize his belief that “This is a people’s war, and the people are entitled to know as much as possible about it.” Cannon helped shape modern communications and inform Americans about the war.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the President

During the years of intensive research and development that preceded the advent of television, Cannon was working closely with the industry to ensure that the company could apply its experience with motion picture, audio and other industries to this new set of requirements. Throughout the ‘40s and ‘50s, Cannon continued to improve the product performance of the connectors. By the 1960s, advancements in connectors allowed even greater retention in the sound quality.

During John F. Kennedy’s presidency campaign in the lead up to the 1960 election, another Cannon product, the UA connector, was a regular feature. This plug was used to connect a special unidirectional mic known as a “shotgun microphone” that was commonly used at large gatherings and would be pointed at members of the audience asking questions, enabling them to be heard on stage without having to pass around a mic.

The mic was onstage with President Kennedy during his first televised press conference in 1961, when he talked about the famine in the Congo, the release of two American aviators from Russian custody, the atomic test ban treaty and took questions on relations with Cuba.

By 1962, the microphone had been used at the 1960 ABC Telecast of the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Parade, CBS pickup of the New York Giants Football Games and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Cannon’s connectors were also versatile – by 1943, the F plug had gone from Hollywood to the Pentagon. In the early 1930s, commercial aerospace was a burgeoning industry, and one in which Cannon saw plenty of opportunity. A single phone call in 1933 ignited Cannon’s role in the aviation industry. A purchasing agent from Douglas Aircraft called to ask James Cannon for an order of solenoids, a type of electromagnetic device that creates a magnetic field. These were needed for the all-metal DC-1 plane. Cannon decided to personally make the delivery, and to bring along a surprise product – the F plug.

The agent was ecstatic – the plug was the answer to a time-consuming problem for workers on the new DC-1 engine. They needed to connect 42 wires from the engine through the firewall before fastening them to proper terminals. The F plug provided a quicker, cheaper and safer way to connect and disconnect the wires – and so Cannon entered the aviation industry.

Several years later, with the build up of hostilities ahead of WWII and the ramp up of military industry, the government asked companies to submit supplier proposals for the new line of AN connectors that would have a standard interface for the Navy, Army, Air Corps and Bureau of Aeronautics applications. Cannon put its hat in the ring and got the contract.

In 1943, Cannon’s “Tri-Services connector” set the standard for military aircraft connections. It became the father of modern day military specifications. Suddenly, Cannon Electric was an in-demand supplier for the American – and Canadian – military, and the company grew by leaps and bounds, both in terms of size, production and creativity.